The sea is becoming a new frontier for airborne-style speed and autonomy. NATO is actively teaching its special forces how to design, build, and operate sea drones to carry out maritime strike missions and other tasks without exposing sailors to risk. This move reflects a broader shift in alliance defense thinking, where unmanned systems extend reach, precision, and resilience in contested littoral environments.

Recent Trends

- Autonomous maritime systems gain traction

- NATO expands USV-focused training

- Defense budgets prioritize sea robotics

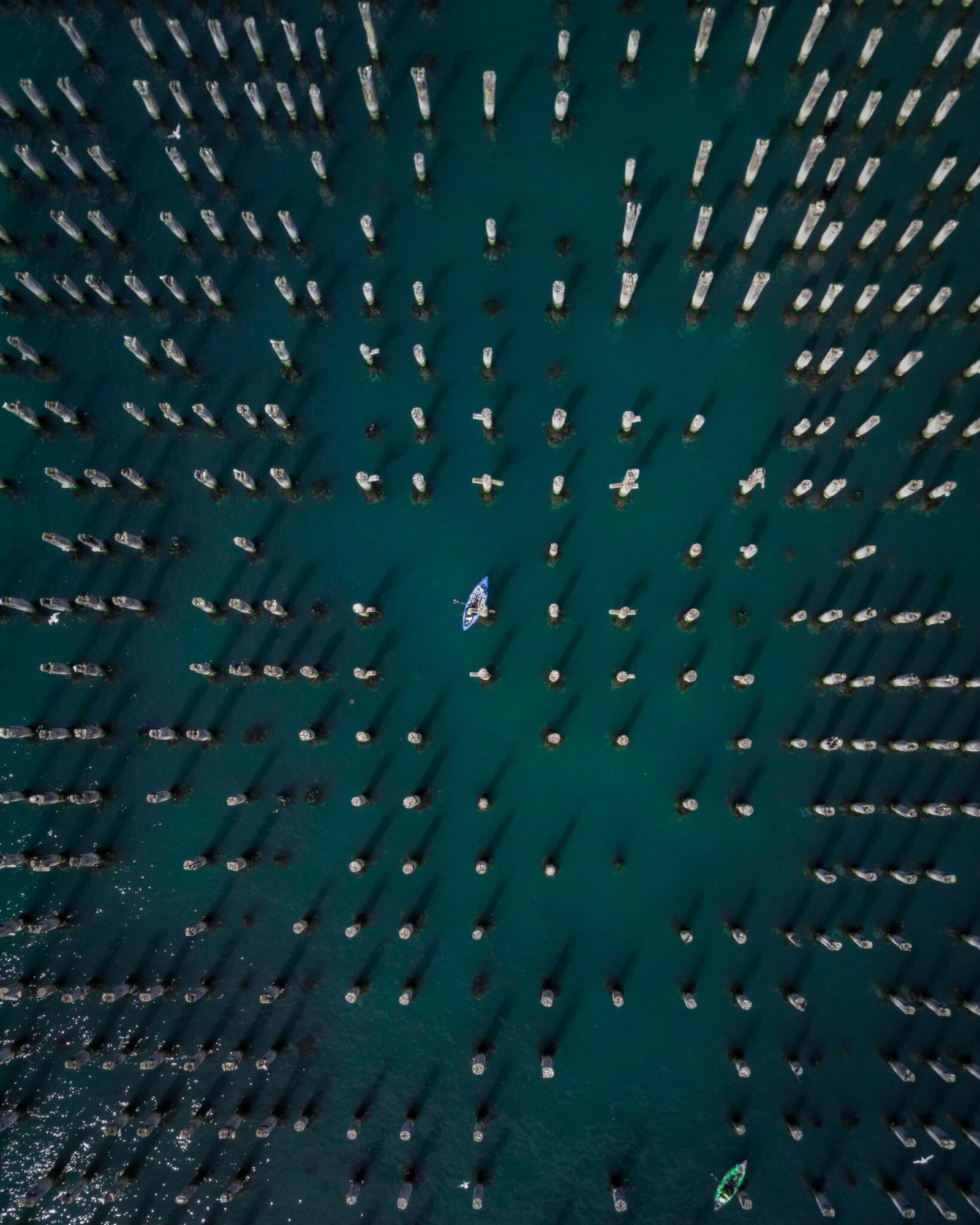

Sea drones, formally known as unmanned surface vessels or USVs, are engineered to patrol coastlines, escorts, and choke points while gathering real-time intelligence. They offer longer endurance, quicker response times, and reduced exposure to danger compared with manned platforms. For defense planners, the message is clear: autonomous maritime capabilities are transitioning from research labs to front-line operations, reshaping how navies project power and protect sea lanes.

In practical terms, the program centers on a pipeline approach: instruction on design principles, hands-on build sessions, and field-testing of USVs under realistic conditions. The capability aims to blend robust hull forms with reliable autonomy software, fusion sensors, and secure comms. The result is a modular system that can be scaled for different missions—from coastal surveillance to targeted surface strikes—without the cost or risk of traditional manned ships. The emphasis on interoperability matters: NATO intends for partner nations to share hardware, software, and tactics, accelerating collective readiness in a rapidly evolving domain of warfare where speed matters as much as accuracy.

According to Euronews, the training marks a concrete step in alliance doctrine as it pivots toward autonomous maritime tools. The emphasis is not just on hardware but on a holistic capability—planning, command-and-control, maintenance, and logistics—so that USVs can be deployed quickly in joint operations. The human element remains essential: operators, engineers, and mission planners must collaborate across borders to ensure that sea drones can safely operate within alliance rules and legal frameworks for use at sea. The takeaway for readers is practical: automation is a force multiplier, but it requires a disciplined, cross-border program to reach its full potential.

Operational Implications

Sea drones bring several concrete benefits. First, they expand surveillance and presence in high-risk areas without exposing crews. Second, they enable persistent patrols that would be costly or impractical with manned vessels. Third, they can act as force-mmultipliers, relaying targeting data or performing coordinated swarms that complicate adversaries’ decisions. These advantages feed into a broader trend: the shift toward unmanned systems across the defense sector, not just in air or land domains but at sea as well. The secondary keywords you’ll hear in policy and industry circles—unmanned surface vessels, maritime drone development, and sea robotics—are moving from niche talk to practical programs with budget and schedule commitments.

Policy and Industry Context

With sea drones entering regular training, questions about rules of engagement, autonomy levels, and export controls rise to the fore. NATO will need clear standards for interoperability, cyber-hardened communications, and safe operation near civilian shipping lanes. There is also a broader industry implication: defense tech providers and smaller nations seek partnerships that unlock access to robust autonomy stacks, sensors, and secure comms. For companies in the defense tech space, the signal is: invest in scalable USVs, robust mission software, and secure data links to stay competitive as alliance programs accelerate adoption of advanced unmanned systems.

What’s Next for the Sector

Looking ahead, expect more joint exercises that test USVs under mixed weather, crowded ports, and contested environments. Expect also a wave of supplier activity around payloads that can be mounted on USVs, from SIGINT and ISR kits to precision strike modules. As the hardware and software mature, the real test will be maintaining safe, reliable operations in complex theaters while preserving alliance-wide legal and ethical standards for autonomous warfare.

Conclusion

Nor is this merely a novelty. NATO’s push to train on sea drones signals a durable shift in maritime defense thinking. By creating a robust USV training and deployment pipeline, the alliance acknowledges that sea robotics will play a central role in securing sea lines of communication in the near future. For operators, policymakers, and industry players, the development underscores a future where the seas are populated by smart, automated teammates that extend reach, reduce risk, and amplify a coalition’s strategic options.